The main features of boom-bust cycles in housing markets are by now all too familiar.

During booms, conditions such as lax lending standards and low interest rates help drive up house prices and with them mortgage debt.

When the bust arrives, over-indebted households find themselves underwater on their mortgages— owing more than their homes are worth.

Feeling the pinch of reduced wealth and access to credit, households, in turn, rein in consumption. At the same time, lower house prices cause investment in new houses to tumble.

Together, these forces significantly depress output and increase unemployment. Non-performing loans increase, and banks respond by tightening credit and lending standards, further depressing house prices and adding to the vicious cycle.

Avoiding boom-bust cycles

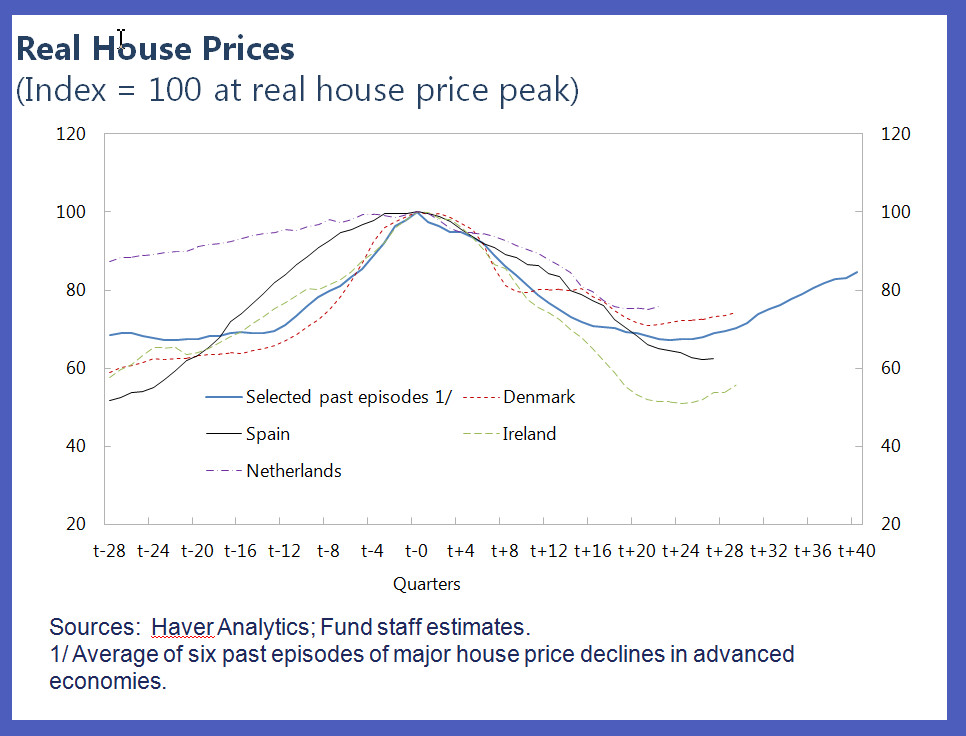

But just because boom-bust cycles are nothing new doesn’t mean that they can’t be avoided, or their effects mitigated. To better understand how policies can promote recovery from such cycles and avoid their recurrence, IMF economists recently completed a new analysis examining the experiences of four European countries—Denmark, Ireland, the Netherlands, and Spain—that suffered real house price declines of 25 percent or more in recent years.

Prices are now rising in Denmark and Ireland, and have begun to stabilize in the Netherlands and likely also in Spain. Nonetheless, these countries are still addressing the legacy of the boom-bust cycle, including significant output gaps—the difference between an economy’s actual level of output and its potential—and private-sector debt overhangs, with household debt-to-income ratios ranging from around 125 percent in Spain to about 300 percent in Denmark (see chart).

Addressing the legacy of the crisis

Closing output gaps and reducing private-sector debt overhang is no easy task, in part due to difficult trade-offs.

For example, if many households cut their consumption and increase their savings to pay down their debt more quickly, this will come at the cost of further depressing output and widening the output gap. A key policy objective should thus be to encourage household debt reduction in ways that minimize the drag on growth.

Supportive economic policies are a first line of defense. For instance, the European Central Bank’s monetary easing during the crisis—along with the preponderance of adjustable-rate mortgages in countries like Denmark, Ireland, and Spain—has helped boost nominal incomes and ease debt-servicing costs by lowering interest rates and boosting growth. Faster nominal income growth makes deleveraging less costly because it allows debt-to-income ratios to adjust more through the denominator (nominal income) than the numerator (cutting spending to reduce nominal debt).

Another approach is to help households access assets that can be used to pay down debt. For instance, the Netherlands adopted temporary tax exemptions that made it easier for parents to help their children pay down mortgage debt. Reforms that allow first-time home-buyers to access their pension savings to finance homes without incurring a penalty have also been used in the United States and Switzerland.

Effective debt restructuring frameworks are also essential to facilitate more rapid adjustment and economic recovery. While countries need to take their specific circumstances into account, a number of measures can help, including:

- regulatory and supervisory incentives to encourage banks to make use of existing resolution frameworks, such as in Ireland where banks must meet targets for offering and concluding sustainable solutions to mortgage arrears;

- establishing effective insolvency frameworks, for instance by promoting less-costly out-of-court workouts; and,

- fiscal incentives, such as easing the taxation of debt relief granted to highly indebted borrowers.

Finally, well-capitalized and provisioned banks are needed to help overcome debt distress episodes. Countries such as Ireland and Spain have benefited from forced recapitalization of banks, following asset-quality reviews and stress tests. Limits on the percent of profits that banks can pay out in dividends have also encouraged banks to repair their balance sheets by boosting capital rather than cutting back excessively on lending.

Lessons for the future

What can be done to reduce the number and severity of housing crises going forward?

- First, remove incentives for excessive debt accumulation by, for instance, gradually reducing the income tax deductibility of mortgage interest. Updating house valuations is also key to ensure property tax payments reflect current valuations, as this avoids subsidizing housing (and thus mortgage debt) and helps lean against the cycle.

- Second, trim distortions in the rental market. This includes progressively reducing rent controls and providing more flexibility in lease contracts, as Spain did in 2013. Such measures can make rental housing more available, thereby reducing the need for households to take on mortgage debt and lessening the economy’s vulnerability to house price cycles.

- Third, use prudential tools to lean against the cycle and avoid excessive debt accumulation. For example, limits on debt-to-income ratios can make it more difficult for borrowers to take on ever-larger mortgages as house prices rise.

While housing crises—just like other crises—are bound to occur, recent experience suggests that countries can take a number of measures early on to mitigate their impact and reduce the likelihood of future crises.

Countries have made progress in this regard, but they should continue to look at available options to strengthen their resilience and prospects going forward, while always taking their specific circumstances into account. An ounce of prevention can help avoid the need for a pound of cure.